Introduction

Back in the 90s, 2D fighting games were pop-cultural phenomena during the golden age of Arcades, much like the status of League of Legends today. As a gamer, I spent countless hours perfecting my skills in games such as Street Fighter (Capcom), and particularly King of Fighters (SNK). However, as a game creator today, I can’t help but hold a critical view of this aging genre as it becomes progressively harder to attract the new generation of players. Even with the release of Street Fighter 6 by Capcom, widely regarded as one of the franchise’s finest entries and set as an example for the future of fighting games, each numbered Street Fighter release since the 4th edition feels like a miracle to revive the genre.

Here is an example of the age distribution within the Street Fighter 6 community, as surveyed in an active Facebook group, with +600 respondents. The most substantial player demographic is within the 35–44 age range, making up 55% of the total, closely followed by individuals aged 26–34, representing 27%. The 45–54 age group constitutes 10%, while the 19–25 years category accounts for 7%. The youngest age group, 13–18, comprises the smallest segment at 1%.

In this article, my goal is to delve into the challenges faced by 2D fighting games that are still designed with an arcade background and outdated cultural archetypes, attracting mostly an aging niche of male millennials who grew up during that era.

PS: note that my analysis primarily focuses on 2D fighting games, excluding sub-genres such as Super Smash Bros or Tekken, which offer their own unique experiences and challenges.

Hard to play, extreme to master

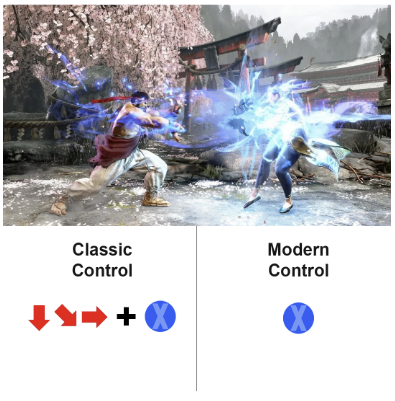

Traditional control: Joystick motion

The difficulty of mastering the controls creates an experience gap between new and older players. When a new fighting game is released, veteran players adapt quickly due to their familiarity with the learning curve from previous titles. In contrast, new players must invest time to learn the controls, and by the time they become proficient, experienced players are already ahead in the competition. This discrepancy can lead to discouragement and cause new players to drop out of the game. In comparison, games like League of Legends have easily understandable controls for all player types, but winning a match is an entirely different challenge.

Now, this joystick motion scheme was well-designed for an arcade experience, but it became problematic when it transitioned to the console gamepad, where the game mechanics are generally based on input rather than joystick motion. While some professional players might adapt to it, it’s not accessible for everyone since you still need to learn and memorize all the commands using the joysticks. It’s like playing chess and having to employ some tricks just to move a pawn.

Modern control: Input motion

To uphold the principle of “easy to play, hard to master,” the designers of Street Fighter 6 introduced a modern control scheme, making it more accessible for new players to trigger the characters’ move set by shifting from joystick to input motion and reducing the number of buttons from six to four. However, it has its disadvantages, such as a lower damage impact.

The modern control is not something new; I reckon it was also utilized in a modded arcade version of the King of Fighter 2002. Because even before, casual players were frustrated to play a fighting game in an arcade without having skilled players around beating them. So this version converted the characters’ special moves into input motions, allowing new players to execute moves more easily and feel empowered enough to compete against skilled opponents. Therefore, more coins in the machine.

While this change might benefit new players, in my opinion, as with the modified version of KOF, it can feel like cheating when two players of the same skill level compete. Nevertheless, only future data will tell how things will evolve, as new players might transition to classic controls to gain the advantages, or inversely.

2D camera layout

The camera may not be an inherent problem, but it’s essential to comprehend its design significance as it plays a role in the overall difficulty of playing a fighting game. Street Fighter drew inspiration from Kung-Fu Master, which featured a horizontal 2D camera-a common perspective in older games. However, for new players accustomed to 3D spatial movement, this camera style might feel unusual when combined with the tricky controls.

The issue with a 2D camera in a fighting game arises when players find themselves trapped in the side corners, shifting the battle dynamic from one based on skill to a game of guesswork. To address this constraint, various games have attempted different solutions. For instance, in Guilty Gear Strive, the game introduces breakable walls in the corner, allowing players to escape from those confined spaces. Another example is seen in Fatal Fury Real Bout, where a second plane is added, providing the ability to jump and evade cornered situations.

To support new players in understanding the game mechanics and adapting to the 2D camera setup, Capcom has ingeniously introduced 3D spatial movement with personalized avatars in Street Fighter 6. Players can utilize this feature in the semi-open world single mode or the online matchmaking room. When a fight begins, the game transitions the avatar from the 3D camera to the familiar 2D camera mode, ensuring a smooth conversion for new players.

Short single mode

When fighting games were made mainly for the arcade, the single or story mode was a quick experience crafted to entertain players until a new challenger put in a coin to play. As much as this approach was useful back then, the single mode didn’t converge well when the genre moved to the console/PC for players who aren’t necessarily competitive, the game content can feel short and not offer enough to understand how to play the different characters,

In my opinion, this mode could serve as a method to instruct new players on the game mechanics while assisting them in discovering diverse gameplay systems for each character’s unique style. Moreover, it could be enriched by an engaging narrative tailored for a console experience, something that Mortal Kombat 11 did well

The new Street Fighter 6 offers a semi-open world mode that allows you to explore the game system through your own avatar. However, it doesn’t necessarily facilitate the transition for new players into the competitive aspect, as you still need to learn separately how to play with the official roster of characters. An alternative approach could have been to combine this semi-open world with the story mode, where you initially engage with the official characters, gradually mastering their techniques from easy to advanced, all while immersing yourself in their individual stories. In SF6, the open-world mode, story mode, and combo mechanics are all separate game modes.

Business model

From low to high barriers to access

In the 90s, fighting games were initially released in arcades and later on consoles. The arcade experience made it easy for many players to join in, as it only required around $0.25 to $1 per play, depending on the machine’s demands and countries. The single mode was satisfyingly short enough to play until somebody else challenged you. Since multiplayer was local, it was also more accessible for players to compete against each other.

Since the genre moved to consoles/PC after the end of the arcade era, most fighting games are sold as premium models, priced at $60. However, the single-mode content often falls short for players who prefer not to play online. For a long time, the online multiplayer wasn’t good enough and lacked adequate support from developers, diminishing the essence of playing a 2D fighting game. Only recently have developers started implementing better net code, as demonstrated in recent fighting games like Street Fighter 6.

From premium to F2P model

To draw in a larger player base, a viable approach could involve transitioning the business model from premium to a free-to-play format, ensuring the exclusion of any pay-to-win elements that might disrupt the game’s competitive balance. Instead, the focus could shift to micro-transactions for selling character customization items or introducing a battle pass system. This way, players can be rewarded with fresh arenas, costumes, and even new characters.

Embracing the free-to-play model would also compel developers to consistently provide ongoing support through live operations, fostering long-term engagement similar to games like Fortnite, League of Legends, or Clash Royale. Riot has announced that their new game Project L will indeed be free to play, which I’m really looking forward to.

Cost vs ROI for professional players

From a professional perspective, getting into fighting games can be relatively expensive compared to the potential cash prize in championships. As a professional player once shared with me, you would need to purchase the game for $60, and invest around $250 in a joystick or a Hitbox, not to mention a good PC setup or console, plus you still need to buy some characters that are not available upon release. On the other hand, games like League of Legends or Dota have a free barrier of entry, where even the most affordable setup can suffice, and the tournaments often offer more rewarding prizes.

In a recent announcement, the Capcom Pro Tour 2023 is set to elevate the competition by offering an astounding $2 million in prize money, with a staggering $1 million reserved for the champion, but still far from other competitors.

Cultural archetype

From the iconic characters Ryu and Ken in Street Fighter to the urban style of Kyo Kusanagi and Iori Yagami in The King of Fighters, or the rock-edgy Ky Kiske and Sol Badguy in Guilty Gear, fighting games revolve around cool characters. Players select their characters not only based on their play style but also as a way to immerse themselves in these virtual personas.

The characters mentioned above share a common thread — they all draw inspiration from iconic cultural figures of the 80s and 90s, spanning from Japan to the US. For instance, Ken from Street Fighter is based on the US kickboxer Joe Lewis, Ryu’s inspiration was Mas Oyama, a famous Kyokushin Karate founder, and Guilty Gear’s rock-edgy style was inspired by the peak years of rock, a music genre that has experienced a loss of popularity in recent times.

The impact this character had back in the 90s or even the early 2000s is not the same as today, as the archetype behind them isn’t as iconic for younger players who are more drawn to inclusive and personalized characters, a constraint that games like Overwatch or League of Legends succeeded in overcoming.

This sense of being outdated is especially evident in new fighting games like KOF16, a game that in the past had cool urban characters inspired by cultural phenomena such as the movie animation Akira. Even Mortal Kombat still uses orientalist mystical Asian archetypes from the 80’s/90’s pop culture.

Street Fighter 5 and 6 did well to introduce new inclusive characters that reflect the diversity of the players today as with Rachid or Kimberly. They also introduced avatar customization. However, I personally would appreciate having greater control over customizing the official characters while still adhering to their distinct art style.

Same spirit, a new horizon

Despite Capcom offering a modern control based on input instead of joystick motion to attract more and younger players, in my opinion, the future of fighting games lies partially in breaking free from the arcade design constraints and embracing the core design of the genre within the new standards.

Actually, this approach of bridging the fighting game system into new standards has already been explored in games like For Honor (Ubisoft) or Sekiro (From Software) as perfectly pointed out in this article. The battle system of these games is built like a rock, paper, scissors system, closely resembling traditional fighting games but with a more friendly and intuitive initial control.

For Honor with its 30 million unique players, is a unique multiplayer game that revolves around progressive skill development and the pursuit of mastery. Unlike traditional fast-paced fighting games, For Honor adopts a slower pace, emphasizing the importance of reading and understanding opponents. Through immersive gameplay and learning by doing, players gradually build their expertise in this combat-centric world.

The game’s strength lies in its accessible mechanics, encouraging players to observe and react to their opponents’ behavior, essentially reading their every move. It’s not about accumulating power or leveling up as I thought at first; instead, the focus is on growing one’s knowledge of the various tools and techniques that can be utilized during duels. With each match, players gain a deeper understanding of their own mistakes and learn to appreciate their enemy’s successes as in a traditional fighting game.

Intuitive and diverse, For Honor offers a sense of competency that is truly rewarding, and victory becomes a reflection of the player’s growth. Moreover, what makes For Honor particularly appealing is its low entry barrier, making it accessible to a wide range of players compared to traditional fighting games, while keeping it hard to develop their skills and reach mastery.

Conclusion

Don’t get me wrong; I’m not trying to bash the fighting games genre. But because this genre is so dear to me, I think honestly that no matter how many new versions of Guilty Gear or The King of Fighters are released, or hoping that a new Street Fighter will miraculously save the genre, or waiting for a potential new fighting games Project L by Riot, as long as this genre relies on an arcade-based design, it will always remain stagnant among a niche of aging players, and it will be challenging to appeal to new audiences who grew up in the post-arcade era, accustomed to intuitive competitive games on PC, console, and mobile platforms as well.

I hope this article will serve as an eye-opener for game developers working on new fighting games and open the discussion to expand the potential of fighting games to new horizons.

Thanks to Fawzi Mesmar and Fei Chen for reviewing this article.

Mark Yassine Ancheta